Pages

-

Beach Read in a Sea Bag!

On Harbor’s Edge is a page-turning Maine island drama set in the early 1900s.

Categories

Recent Posts

-

A Maine Island Story for the Holidays

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr On Harbor’s Edge: A Maine Island Story for the ... -

Flying Cold

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr As the waters along the coast and between islands... -

Life Flight

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr The night Evan Hopkins’ truck left the road... -

Life Patterns

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr For artists Eric Hopkins and Peter Ralston, islan... -

Island Rescue!

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr Fifteen Maine islands are inhabited year-round wh...

-

-

Say Ello

Fire Danger

North Haven to China

![]() February 24, 2012

February 24, 2012

Author : Kate Hotchkiss Taylor

Author : Kate Hotchkiss Taylor

![]() Category: History

Category: History

![]() 0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s)

Lindberghs Captivate the World in 1931

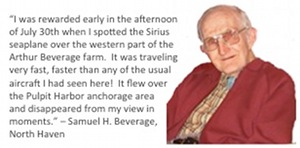

"An hour and a half before they took off, you could have walked across the Thoroughfare on the rowboats," wrote Ellen Pratt (1906 - 2000) of the day Anne Morrow and Charles Augustus Lindbergh left North Haven on what became the Great Circle Route to the Orient.

Photo courtesy North Haven Historical Society

That was July 30th, 1931, described by Pratt as “a perfectly beautiful day”. Aviator hero Colonel Lindbergh and his pilot-navigator-radio operator wife Anne had just spent a respite at her family’s summer home surrounded by friends and relatives. The trip originated in Washington, D.C. The flight officially started in New York. For Anne and her fellow islanders, the true beginning of this startling journey was firmly anchored in the Fox Island Thoroughfare between two islands.

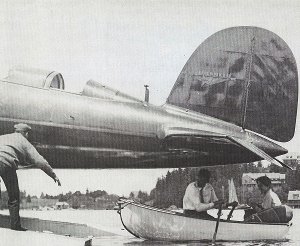

Alfred Burke guards the Sirius on its mooring in the Fox Island Thoroughfare. --Photo courtesy of the North Haven Historical Society

Charles Lindbergh comfortably splices line aboard the Lockheed Sirius before he and Anne depart the Fox Island Thoroughfare on their pioneering China flight. --Photo courtesy of the North Haven Historical Society

North Haven was a treasured place for Anne filled with childhood memories, and it became the base from which Anne copiloted her second record-setting flight. This home was so dear to her that according to her sister Constance Morrow Morgan, (1913 – 1995), Anne worked the hardest on writing chapter four “North Haven”, for North to the Orient published in 1935. The book became the number one bestseller in the United States at 55,000 copies sold that year, won the National Book Award, and was the first of several literary triumphs for the pilot-writer-mother.

Of North Haven Anne writes, “The visit was an emotional springboard, and, as such, was marked with an importance far greater than its brief hours might warrant.” Of their departure she adds, “The day was hard and clear and bright, like the light slanting off a white farmhouse. The island falling away under us as we rose in the air lay still and perfect, cut out in starched clarity against a dark sea. I had the keenest satisfaction in embracing it all with my eye. It was mine as though I held it, an apple in my hand.” Little wonder she held the island so lovingly as they flew north: The couple’s one year old son, Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr, was ensconced in the haven of her family’s white farmhouse by the sea.

Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh board the Sirius with a helping hand from Joe Burke of North Haven. The couple charted and flew the great circle route to China, a course still followed by airliners. --Photo courtesy of the North Haven Historical Society

Anne was just 25 at the time she flew 10,000 miles to

---Photo by Nan Lee

Water Landings in Five Countries, a Flood, and an Accident

Safe ocean harbors, lakes, and even rivers were critical to the Lindberghs’ success and survival during their flight. As storied in Mrs. Lindbergh’s North to the Orient, after departing from North Haven the couple flew to Ottawa, during which Anne had what she describes as her “first successful day” on the radio. That evening Colonel Lindbergh mapped their route across Canada with the help of concerned colleagues. Anne describes the scene in signature candor: “An absorbed group of aviators, travelers, explorers, meteorologists, surveyors, and scientists – men who knew Northern Canada as no other group in the world – stood around him arguing.“ When one of the experts said he would not take his own wife on a particular leg they were considering, Mr. Lindbergh reminded him that his wife was “crew”, a professional confidence Anne was “even more flattered” by than the chivalry expressed by the expert advisor. Charles was fierce about safety in the air, land, and on water, a characteristic he was known for as a father as well as flyer. Even so, since they were heralding new ground in an infant industry, danger was inherent, stalking them constantly and most often in the form of fog. After listening to his Ottawa-based team members’ input and objections, Colonel Lindbergh secured the Canadian leg of he and his copilot’s great circle route.

While the trip took them to 18 more locations, Anne focused on key stops in her writing starting with Canada’s Baker Lake, “ . . . a gray glassy lake, bounded by gray bleak shores a little higher than the marshes.” From Baker Lake they followed the Canadian shore along Amundsen Gulf on the Beaufert Sea, putting them in a river near Aklavik. Next they landed in a lagoon at Point Barrow, “the bleak northern top of Alaska”, after dancing dangerously with thick, incessant fog. From there they arrived at the mining town of Nome, another ocean landing during which they raced the darkness to seek a safe night in an unknown harbor on the Bering Coast. On to Kamchatka, Russia after flying over the tiny island of Karaginski, where Anne was able to communicate in French rather than the beginner Russian she had learned in preparation for the trip. After soaring along the chain of islands that connect the Kamchatka Peninsula to the big northern Japanese island of Hokkaido, more fog banks haunted the skies, as if hunting them down. Such weather required an emergency landing in open ocean 200 meters on the lee side of Ketoi Island after multiple, frightening, failed attempts at a Buroton Bay landing. “Does he really think I enjoyed his game of tobogganing down volcanoes?” laments Anne that day. Despite their rough landing in choppy seas, Anne’s subsequent experiences in Japan were worthwhile on many levels. Morgan explains that while her aunt was fascinated by all the places they went and the people they met, the philosophies and aesthetics of Japan would have a lasting impact on Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s life and writing.

Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh arrive in Japan --Photo courtesy of the North Haven Historical Society

Anne writes about Osaka next, a city made particularly memorable when her husband discovered a “good-sized boy of 18” hiding in the forward cockpit! Anne worried about what would happen to the young stowaway, a fellow unhappy at home and hoping to land himself in the United States, compliments of the Lindberghs. The couple was, of course, en route to China; if they had even managed to take off with all that extra weight, the young man would have found himself in the wrong country if he had succeeded.

A teenager photographs her father, US Ambassador Willis Peck, welcoming the pilots. Damaris Peck Reynolds' photo printed by permission of Steve Harnsberger, flood31@gmail.com

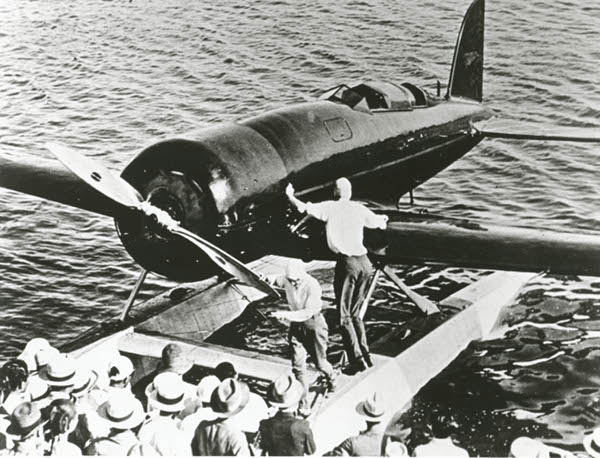

A subsequent botched attempt at lowering the plane back

Charles Lindbergh attaches lines to rescue the Lockheed Sirius from the Yangtze River --Photo Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

While surely ecstatic they survived jumping into such reckless and potentially infectious water, the couple was just as surely devastated over how seriously their plane was damaged. They would have to take a ship home to America, and that meant more time away from their beloved son. News of this major mishap reached family and friends on North Haven and elsewhere in the country quickly, causing concern and disappointment. Given the Lindberghs’ accustomed speed of travel, it must have been extremely frustrating for them to move so slowly. To make matters worse, Anne’s father, Ambassador Dwight W. Morrow, unexpectedly passed away before they could return. North Haven resident Lewis Haskell sums up the collective feeling well: “Later we heard that they got in trouble in China in the floods that were going on there, fell in the Yangtze River, and got the plane all banged up. People worried. It seemed a terrible comedown that they took a boat home. He should have flown home.”

Anne and Charles Continue Staggering the World

The Lindberghs did not stay grounded for long, and by 1933 they installed a more powerful engine in the Sirius in preparation for an Atlantic Survey Flight. Again departing from the Fox Island Thoroughfare, this pioneering trip took them to Labrador, Iceland, Greenland, Europe and then on to Africa, South America, and islands between. Ten days of this journey is described in vivid and disarming detail in another best-selling and award-winning nonfiction book by Anne, Listen! The Wind, published in 1938. During this historic, highly productive flight a young Greenland boy christened their Lockheed Sirius 8 Tingmissartog, meaning “one who flies like a big bird”.

In their first flight to the Orient of 1931 Anne and Charles Lindbergh did even more than establish another new aviation route, or set another record. They enhanced US-China relations, helped those stricken by the massive flood there, and represented the very best of youth and promise while capturing the imagination of the world. In addition, long before the feminist movement really took hold in the United States, Anne Morrow Lindbergh broke through glass ceilings neither she nor Charles acknowledged as she flew right through them. Quietly capable and naturally unassuming despite incredible achievements so young and throughout her life, Anne was additionally supported by her husband in changing the paradigm as to what women could do outside the home. There does not seem to be any conscious effort on their parts to forward women’s equality – that just came naturally to both Anne and Charles, in a matter-of-fact, practical way as if who could think otherwise anyway. Indeed, Anne was often humored by members of the press who would make up what she was wearing, not actually paying attention to her real clothes! Observes Morgan of the Lindbergh’s copiloted flights, “The newsreel footage of a married couple working in such equality in a professional situation would have a huge impact on the American imagination of how men and women might work together."

As so aptly stated by island resident Garrison Norton in a letter to the North Haven Historical Society decades ago, “Charles and Anne staggered the world between them.”

Sincere thanks, credit, and acknowledgement for this story goes to the North Haven Historical Society and its supporters, Ms. Margaret Eiluned Morgan, Ms. Reeve Lindbergh and her book Under a Wing published by Simon and Shuster in 1998, China Historian Mr. Steven Hansberger, The Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, Lindbergh’s Chart Flood Area in China, September 21, 1931, by New York Times journalist Hallett Abend, Yale University’s Chief Research Archivist and Lindbergh historian Judith Schiff, and publisher of Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s North to the Orient and Listen! The Wind: Harcourt, Brace and Company of New York (pages 46, 52, 58, 59, 157, and 207 of North to the Orient quoted directly).

About the author--

Kate is a photographer, writer, and global business consultant who speaks Mandarin. Kate lives with her husband and two teenage sons on islands North Haven, Isle au Haut, and the water between. www.taylorwrite.com.

COMMENTS

There are no comments yet!