Pages

-

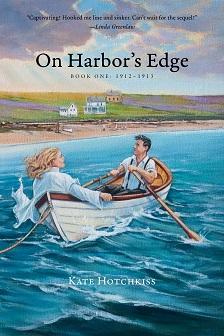

Beach Read in a Sea Bag!

On Harbor’s Edge is a page-turning Maine island drama set in the early 1900s.

Categories

Recent Posts

-

A Maine Island Story for the Holidays

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr On Harbor’s Edge: A Maine Island Story for the ... -

Flying Cold

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr As the waters along the coast and between islands... -

Life Flight

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr The night Evan Hopkins’ truck left the road... -

Life Patterns

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr For artists Eric Hopkins and Peter Ralston, islan... -

Island Rescue!

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr Fifteen Maine islands are inhabited year-round wh...

-

-

Say Ello

Fire Danger

Return of the Natives

![]() February 20, 2012

February 20, 2012

Author : Charles Curtin

Author : Charles Curtin

![]() Category: Environment

Category: Environment

![]() 0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s)

Bringing Forage Fish Back to the Islands

In a world where so much of fishing is a zero-sum game, commercial fishermen compete to survive on ever dwindling stocks of species. As the cornucopia of the sea becomes an increasingly distant memory, it is

Trucks loaded with 3000 live alewives disembark at the North Haven landing. The offspring of these fish will return by sea in five years to regenerate a native North Haven alewife population. Fisherman Adam Campbell donated the cost of barging the precious cargo. --Photo by Charles Curtin

Last spring 3,000 adult fish captured and transported from Maine’s Kennebec River were introduced to Fresh Pond. After spawning they headed back to sea and will eventually return to Kennebec waters to spawn again. Their most recent spawn, however, were conceived in Fresh Pond so this new generation is imprinted to North Haven. Some of the young natives will will stay in the pond, but most will head out to open ocean and may travel as far south as the Carolinas before turning back five years hence. When these fish return they will mark the beginning of renewed North Haven alewife spawning runs with anticipated exponential population growth. As stated by alewife harvester Jeffrey Pierce, “Giv’em a chance and they’ll grow like weeds.”

While there is high hope for the future North Haven alewife

Jeffery Pierce (left) of Alewife Harvesters of Maine and fisherman Adam Campbell stop to pose while measuring a fish passageway. --Photo by Charles Curtin

Spawning adult alewives released into Fresh Pond mark new beginnings for a native North Haven population. --Photo by Kate Hotchkiss Taylor

In contrast, the program to reintroduce smelt is a collaboration of the North Haven Community School, DMR biologist Claire Enterline, schoolteacher Kristen McGovern and her students, with me serving in a coordinating role. Here again, fishermen were key: The smelt program emerged through the encouragement and engagement of Campbell and Peter MacDonald who inspired my thinking on restoring anadromous fish. Several years ago MacDonald approached me during a ferry ride and asked, “Why the heck are you working to help sustain cod stocks way offshore, when there are local sources of fish we lost right here on North Haven?” The smelt were, indeed, a local tradition on the island for centuries before disappearing in the mid-1970s. The smelt-rearing program is based on a technique developed by the University of Massachusetts. In this scenario the fry are hatched at the Community School before release in local streams come spring. Unlike migrating alewife, the smelt appear to stick around, and may stay in the area for much of their lives.

Photo of a restored alewife run--an image to be seen again on North Haven thanks to forward thinking fishermen, residents, and scientists working together. --Photo by Charles Curtin

The two species are a study of contrasts: alewife migratory, smelt more local; alewife spawn in fresh water, smelt in brackish water; while alewife are highly desirable as food for cod, smelt seem to be preferred by salmon. Despite their differences, it is clear that these species can restore a cultural and ecological integrity along the coast—reconnecting people with their environment, and the ocean with the land. Perhaps most importantly is a returning message of hope for the future.

Photo by Philip D. Curtin

About the author--

Charles Curtin is a restoration and landscape ecologist who works globally on marine and terrestrial conservation programs ranging from the American West to East Africa and the Gulf of Maine. He teaches environmental studies at Antioch University in Keene, New Hampshire, and lives year round on North Haven Island.

COMMENTS

There are no comments yet!