Pages

-

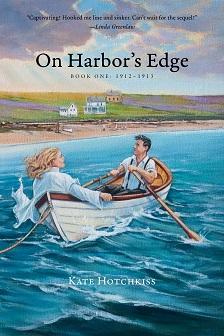

Beach Read in a Sea Bag!

On Harbor’s Edge is a page-turning Maine island drama set in the early 1900s.

Categories

Recent Posts

-

A Maine Island Story for the Holidays

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr On Harbor’s Edge: A Maine Island Story for the ... -

Flying Cold

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr As the waters along the coast and between islands... -

Life Flight

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr The night Evan Hopkins’ truck left the road... -

Life Patterns

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr For artists Eric Hopkins and Peter Ralston, islan... -

Island Rescue!

Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Google+ Tumblr Fifteen Maine islands are inhabited year-round wh...

-

-

Say Ello

Fire Danger

Life Flight

![]() July 23, 2013

July 23, 2013

Author : Maine Island Living with Dr. David Urion

Author : Maine Island Living with Dr. David Urion

![]() Category: Community

Category: Community

![]() 0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s)

The night Evan Hopkins' truck left the road, an island EMS team, including EMTs, fire department, and a nurse practitioner arrived within minutes.

“This was the most serious call I have ever been

LifeFlight’s two Agusta helicopters. They need three. -- Photo courtesy of Vertical Magazine

Tragically, Hopkins’ injuries were such that he would not have survived, even if LifeFlight had arrived within minutes. It will be years before the island community recovers from losing this beautiful young man, and for some, the recovery will never be complete. Just twenty years old and the youngest of a large family, Hopkins’ smile was positively infectious.

For the EMS crew, the trauma of pulling a beloved member of their community out of his vehicle with no hope of survival left additional scars.

Brandy Dupper-Macy

“When we first arrived on-scene and I got word that LifeFlight was unavailable, a sense of hopelessness washed over me,” said Dupper-Macy. “It’s been hard to shake the deep-seated sense of despair I felt that night, but it has also motivated me to work harder at The LifeFlight Foundation.”

The number of calls to LifeFlight has steadily increased over the last 15 years. As the organization reaches capacity for its two helicopters, a third aircraft has become necessary to meet the growing need. On the mainland, the LifeFlight crew via ground ambulance can answer some life-threatening emergencies if the helicopters are already busy. North Haven and other islands off Maine’s coast do not have that luxury.

“We’re incredibly lucky to be staffed with a nurse practitioner on our calls,” said Dupper-Macy,

North Haven’s EMS crew await arrival of LifeFlight during a Memorial Day emergency. Photo by Rowan Wade

"The staff at the Foundation office are dedicated to the mission of adding a third aircraft to help make sure LifeFlight can continue to respond when it’s needed most. I couldn’t help Evan that night, but I can take this devastating accident and make it into a ray of hope for the next person who makes the call for LifeFlight—he’s going to help me save thousands of lives. That’s what gives me peace in all of this.”

Inspired by and grateful for the services of treasured island EMS and fire department crews, Dr. David Urion stood in for Reverend Dave Macy at North Haven’s Baptist Memorial Church on May 5, 2013 to thank and pay tribute to first responders here and elsewhere. Reverend Macy is himself a first responder who drives the ambulance.

Dr. Urion presented the following moving sermon:

In the names of God: Creator, Redeemer, Sustainer. Amen.

“I do not give to you as the world gives.“

It is an enormous, and very humbling, privilege to be asked to this pulpit, on this island, at this time, to offer public appreciation and open gratitude to all the first responders in this community. Over the interval since I was first asked to come and preach at this event, the city where I work has also learned something about first responders, and what the full measure of their gift to us all represents.

For quite a bit of my year, I work as a consulting physician in intensive care units -a setting that is tidy, well-equipped, well-lit, has a roof and walls, and lots of other people to help me do whatever I do. I see patients that have been put in gowns, often washed up, and where what we are doing is usually quite clear. I don’t fish people out of cars, or work by the side of the road, or stand in the pouring rain, or run into burning buildings, or have various body fluids sloshing about in the mix.

And I work with the gift of anonymity. I do not know, nor am I known, by any of the families under my care. I look at the face of an injured child or a distraught parent, and I look into the face of a fellow human, a brother or sister in our common family. I am not asked to look upon the face of someone I have known for years in the midst of responding to a crisis.

I invite us today to ponder, for a moment, the enormous gift we are given by those among us willing to be first responders, and I would like to acknowledge how very foundational they are to all of us, any of us, living in a community. I then want to consider three aspects of this gift: call, loss, and justice.

Consider, for a moment, what the implications of having first responders around us actually means. We are of a nature to grow old: old age is unavoidable. We are of a nature to become ill: illness is unavoidable. And we are of a nature to die: death is unavoidable. And so these are the realities of all our lives, sooner or later. We are able to go about our business, on a daily basis, with some small modicum of confidence because as part of our social contract, some of us are willing to do extraordinary things to help the rest of us in those very circumstances: aging, illness, dying. Some of us are willing to put our own desire for leisure, comfort, and even sheer physical safety aside for a time in order to benefit those of us who are in danger, sorrow, sickness, or trouble. Our very lives in a community – be that as relatively isolated a place as an island, or a large metropolitan area – are made possible, at some level, by the willingness of some of our fellow citizens, our brothers and sisters in our large, fractious, and complex human family, to take care of the rest of us.

This is an astonishing fact. When you come to the conclusion that we humans are, in a very technical biological sense, a social species, like bees or ants, you then go about looking for evidence that this is a good thing. The existence of people willing to be first responders is one very important piece of such evidence. This is a very good thing.

I stand in even greater wonder and admiration for people who volunteer to be first responders. That is, people who earn their living doing something else, but are willing to give up some of their free time, and serve the rest of us as volunteer first responders. I grew up in such a place. The term that was used for the people who came running in my small town was “call fire fighter”.

Call. It has a deep resonance in our communities of faith as well. Our scripture is filled with stories of call. Samuel is called to the service of the Lord as a prophet quite literally, when he hears a voice in the temple at night, while holding vigil for the lamp. Jesus calls the twelve, the central figures being commercial fishermen, an occupation well known in these parts. And Mary is called by the archangel Gabriel, into a life and a pregnancy she can barely fathom.

For a call to be remembered, literally re- membered, made part of our common story, it must have a response. Someone must say yes. We have no idea how many young women the angel visited before Mary said yes, be it with me according to your will. How many young women gave the sane response, the logical response, put their hands over their ears and hummed loudly, or ran screaming in the other direction, when the angel gave the call? How many boys heard the voice in the night in the temple on their shift, and rolled over, pulling the covers over their heads, and went back to sleep? How many other fishermen refused to leave their boats and follow an enigmatic rabbi onto the land? We will never know. We only know the stories of those who said yes. And we know that this yes made their lives immeasurably more complex, and difficult, and also immeasurably richer and deeper, for having said yes.

Our lives are all made safer, and better, by all of you here today who said yes – to the request of the town, to your fellow citizens, to some sense of adventure, to some sense of responsibility. In the end, like most moral choices in the midst of being exercised, why you said yes doesn’t matter all that much. Those being rescued, soothed, saved, are just grateful you said yes. And we all stand in admiration of that call, and your response.

There is, in all this, also a loss, or a series of losses, we must acknowledge. There are the obvious losses of free time, some money, and the presence of the electronic leash on your belt.

There are the losses of dinners unfinished, picnics upended, tasks abandoned midstream, birthday parties ruined; these losses are ones you take on, for the benefit of the rest of us. We need to remember that, and thank you.

The harder losses, though, are the inner ones. Whether we openly grieve after an accident doesn’t turn out well, or a resuscitation is unsuccessful, or a building is lost, or whether we suck it up and move on and say that’s just how it is, whether we sit on a rock and weep or demonstrate the quiet resolve for which this coast is justifiably famous, there are wounds on the heart and in the soul, if you do this long enough. To pretend otherwise flies in the face of reality. I have been a physician for over thirty years, and I run a training program for young physicians, and I know there are always losses that haunt us. The ones you thought you had saved, and then lost, or the ones where you knew from the get-go this was a lost cause, even with all your skill and cunning and energy, and you still tried with all your heart and soul and strength. The ones you still dream about, or see in your minds’ eye, or on bad days, out of the corner of your eye, just sitting there. If you do this long enough, you are what the late Henri Nouwen referred to as a wounded healer.

This is the price paid for doing this work. This is the price those of us who benefit from your labors implicitly ask of you, whether we know it or not. The gospel today hints at this. The work you are given to do, as a first responder, is a huge privilege. Serving people offers a kind of exhilaration and delight that little other work does. But it takes its toll. It will take it out of your hide. So when Jesus says, “ I do not give to you as the world gives to you”, I think this is what he is saying. This work is a great gift, but it takes you to places other people don’t go. And I think we can remember another story from the gospel of John when we find ourselves in that strange country of loss and darkness. When Jesus hears of the death of his friend Lazarus, we do not get a

sermon on heaven, we do not get a meditation on how every tear will be wiped away, we do not receive some promise of a beautiful place where we will all be together again. When Jesus hears of the death of his friend Lazarus, he sits on a rock, and weeps. “Jesus wept.” The shortest verse in our scripture can be a good companion in the midst of such a time. Jesus, Emmanu-el, God with us, knows a very human moment of suffering and loss, and reacts as humans do. It is paraphrased in one of my favorite hymns. “And when human hearts are breaking under sorrow’s iron rod, then we find that self-same aching, deep within the heart of God.”

So in the midst of this appreciation for what you do, we must be honest and acknowledge that we have put your hearts and souls in harm’s way in this work, and that cannot be helped.

Finally, there is a notion of justice embedded deeply in this work you do. Certain Hassidic Jews have a legend of the 36 just people. They believe that at any given moment in human existence, there are 36 just people, on whose shoulders the pillars of the world rest, metaphorically. They believe that were it not for the very existence of these 36 people, the world would suffocate in a strangled cry of loss and pain and hurt. These people are not the great princes of this world, not rich people with vast fortunes, or famous artists, or other powerful people. They are anonymous, quiet, very ordinary people who yearn to do the right thing, the moral thing, the just thing. In the legend, it is not their success in doing good which keeps the world going, it is their desire to do good that carries the day. The very fact that they want to do good, to do the right thing, is what makes them so important in the balance of the universe.

I love this legend, not because I particularly believe, or disbelieve it – in the end, it seems as plausible as any explanation for why the universe is still here even in the midst of chaos and tumult and greed and violence. I love it because it suggests that a good intention to do a right act means something. That is what distinguishes us from other inhabitants of this planet, other species. Not our art, as wonderful as it is, or the marvelous engines of commerce, as amazing as they are to consider, or our political systems, or our science, or any of the

thousand, thousand things pointed to as human culture. What makes us who we are is this, I think. A desire to do good. A fervent wish to be useful.

The poet Marge Piercy said it this way, in her poem:

To Be of Use

The people I love the best

Jump into work headfirst

Without dallying in the shallows

And swim off with sure strokes almost out of sight.

I love people who harness themselves, an ox to a heavy cart,

Who pull like water buffalo, with massive patience,

Who strain in the mud and the muck to move things forward,

Who do what has to be done, again and again,

Who go into the fields to harvest

And work in a row and pass the bags along,

Who…move in a common rhythm

When the food must come in or the fire be put out.

The thing worth doing well done

Has a shape that satisfies, clean and evident.

The pitcher cries for water to carry

And a person for work that is real.

For the very real work you do, Thank you.

Amen.

This story took longer to prepare than planned. Maine Island Living was scheduled to secure photos during an island LifeFlight ground safety course, but that training was cancelled when both LifeFlight helicopters were called to time sensitive, life threatening emergencies – one to nearby Vinalhaven Island and one to a mainland town.

LifeFlight is called upon every six hours, on average. Last year LifeFlight handled 1,533 transports from 142 Maine towns. As the need for rapid transport increases, the need for a third aircraft becomes more and more critical.

Paramedic Kim McGraw cares for a little boy during a LifeFlight transport. --Photo courtesy of LifeFlight of Maine

LifeFlight of Maine is a non-profit organization that relies on the generosity of donations to fund their aircraft and medical equipment to care for critically ill and injured patients. LifeFlight currently has two Agusta helicopters and is seeking funds for a Fixed Wing aircraft and third helicopter to ensure LifeFlight is there when the call for help is needed most. To help this worthwhile cause, go to: www.lifeflightmaine.org

Dr. David K. Urion, is the Director of Education and Residency Training Programs in Child Neurology and Neurodevelopmental Disabiities in the Department of Neurology at Boston Children's Hospital, where he holds the Charles F. Barlow Chair. He also serves as the Director of Behavioral Neurology Clinics and Programs at Boston Children's Hospital. At the Harvard Medical School he is an Associate Professor of Neurology, and served as the first Faculty Director of the Division of Service Learning.

Dr. David K. Urion, is the Director of Education and Residency Training Programs in Child Neurology and Neurodevelopmental Disabiities in the Department of Neurology at Boston Children's Hospital, where he holds the Charles F. Barlow Chair. He also serves as the Director of Behavioral Neurology Clinics and Programs at Boston Children's Hospital. At the Harvard Medical School he is an Associate Professor of Neurology, and served as the first Faculty Director of the Division of Service Learning.He is a seasonal resident of North Haven for the past 25 years.

Maine Island Living thanks Dr. David Urion for his permission to print his sermon, and gratefully thanks all EMS crews and their supporting families on and off islands for their precious service saving lives—without regard of peril to their own.

COMMENTS

There are no comments yet!